You hand back a test and notice your gifted student with the highest score looks devastated. They didn’t get 100%, and to them, that feels like failure.

Many gifted students move through primary school with ease, rarely encountering a task that truly stretches them. This early success can mask a hidden risk. When they eventually “hit a brick wall” of challenge in high school, university, or beyond, they often lack the emotional tools to cope with struggle. Instead of seeing difficulty as part of learning, they may interpret it as proof that they are not as capable as they thought. Some give up rather than risk failing again.

Research shows this cycle of perfectionism and avoidance is common in gifted learners and can lead to anxiety and underachievement if resilience is not intentionally taught (Gross, 2004; Neumeister, 2004). Teachers can play a powerful role in shifting this pattern by making challenge a normal part of classroom life and guiding students to see mistakes as opportunities for growth.

Understanding Perfectionism in Gifted Students

Perfectionism in gifted learners is often misunderstood. On the surface it can look like motivation and high standards. In reality, unhealthy perfectionism is more about fear than drive (Neumeister, 2004).

These students link their self-worth to flawless performance. Even small mistakes feel like failure. In class this may look like a student refusing to attempt a problem unless they are certain, or handing in nothing at all rather than risk being wrong.

Some mask their fear through disengagement. Others constantly erase, rewrite, or avoid tasks they cannot guarantee success in.

Miraca Gross’s longitudinal study found that when students are not stretched, they are unprepared for real challenge later on. Without early chances to build resilience, many disengage or underachieve when difficulty finally arrives (Gross, 2004).

Resilience, then, is not about lowering expectations. It is about helping gifted learners cope with struggle in a healthy way and see mistakes as part of growth.

Why Resilience Matters in Gifted Students

Resilience is the ability to recover from setbacks and keep going when things feel tough. Many gifted students have not had enough chances to practise this skill. When challenge finally arrives, it can feel overwhelming, and some give up (Ronksley-Pavia, 2020).

Growth mindset thinking helps shift this response. When students believe their abilities can grow with effort, they are more likely to persist and take risks (Dweck, 2006). For gifted learners, it means moving from “I should always get this right” to “I can learn through challenge.”

But growth mindset is not a magic fix. Research shows generic interventions often make little difference for high-ability learners (Sisk et al., 2018). What matters is combining mindset language with real opportunities for challenge and support.

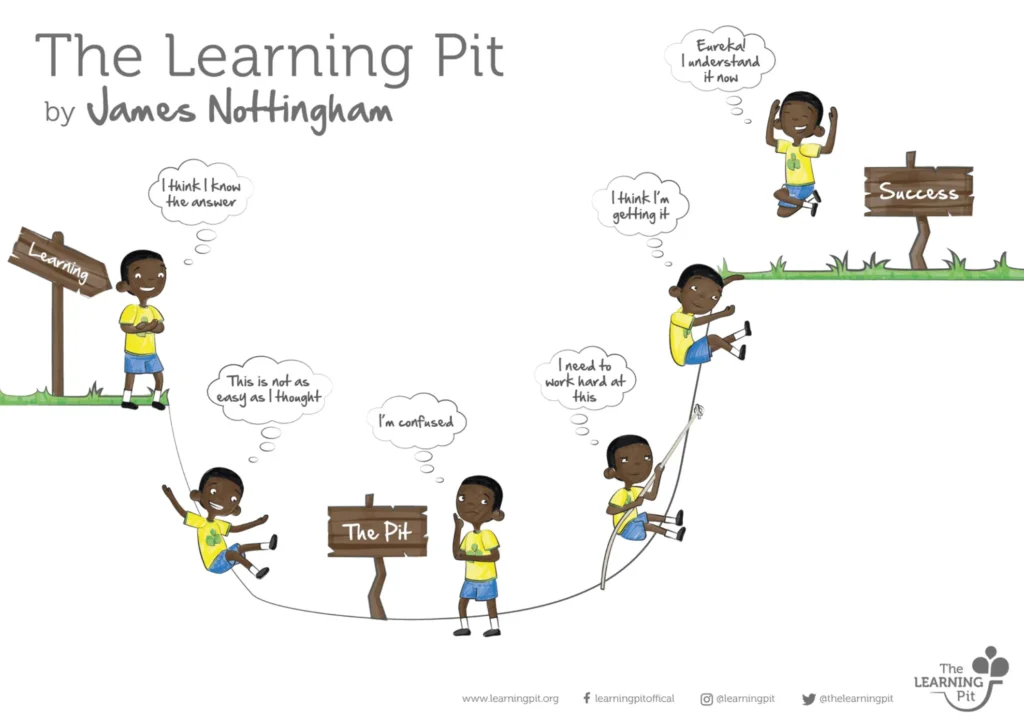

A helpful way to show this is James Nottingham’s Learning Pit (2010). The model illustrates that confusion and frustration are normal at the start of learning. With persistence and strategies, students climb out of the pit with stronger understanding. For gifted students, it reframes struggle as a natural and valuable part of growth.

Teaching Strategies to Build Resilience in Gifted Students

- Model mistakes openly. Gifted students often believe adults never get things wrong. Share times you made an error, how you fixed it, and what you learned. This helps students see mistakes as part of progress, not proof of weakness.

- Normalise productive struggle. Create a culture where challenge is expected. Talk about “stretch moments” and let students know it is normal to feel uncomfortable when learning something new (Neihart et al., 2016).

- Celebrate effort as much as outcomes. Praise persistence, creativity, and risk-taking. For example: “I like how you tried three different ways before solving this,” instead of “You’re so smart.” Over time, this shifts students’ focus from results to growth.

- Provide tiered challenges. Offer tasks with different levels of complexity so students always have something that stretches them. Gross (2004) found that without meaningful challenge, gifted students are more likely to avoid risks later.

- Teach coping strategies. Introduce tools like self-talk, mindfulness breaks, or reflection prompts. These strategies help students manage the anxiety that comes with imperfection.

- Use the Learning Pit as a visual guide. Show students Nottingham’s (2010) model of moving into and out of the pit. Ask them to reflect: “Am I at the bottom of the pit or climbing out?” Pair this with journaling so they can see their growth over time.

- Model self-compassion. Gifted learners can be their own harshest critics. Use language that shows it is okay to be kind to yourself when things do not go as planned.

Classroom Activities to Encourage Risk-Taking

Thinker’s Keys. Use prompts that ask students to generate multiple solutions. These encourage safe risk-taking and help them practise creativity.

Growth Through Challenge Posters. Display this free set of 10 classroom posters to remind students daily that challenge feels tough but leads to growth.

Low-stakes puzzles. Try logic puzzles, riddles, or Brain Strainers. These allow students to practise persistence without the pressure of grades.

Group reflection circles. Invite students to share times they felt “in the pit” and how they worked through it. Peer stories help normalise struggle.

Quick challenges. Offer short, time-bound tasks with no single correct answer. For example, “List as many uses for a paperclip as you can in three minutes.” These help students practise risk-taking in a playful way.

Role-reversal tasks. Ask students to solve problems from another perspective, like “How would an inventor approach this?” This encourages flexible thinking and reduces the fear of one “right” path.

Linking to Underachievement

Perfectionism does more than cause stress in the moment. Over time it can directly contribute to underachievement. Gifted students who fear failure may avoid new or difficult tasks. Instead of pushing their abilities, they choose the safer path and stop short of their potential (Neihart et al., 2016).

This avoidance becomes a pattern. Students who are used to success can interpret one setback as a sign that they are “not really gifted.” Some withdraw from enrichment opportunities, others underperform in areas where they once excelled.

Another layer is masking. Gifted students who also have learning differences may appear “average” because their strengths and challenges cancel each other out. In these cases, both the giftedness and the difficulty remain invisible (Ronksley-Pavia, 2015, 2020). Without intervention, these students are at high risk of underachievement.

For more on masking and 2e learners, read Making Twice-Exceptional Students Visible in Policy and Practice.

Building resilience interrupts this cycle. When teachers make struggle part of the learning process, students begin to see mistakes as opportunities rather than threats. Over time, this shift not only reduces perfectionism but also prevents the downward slide into disengagement.

Practical Takeaways for Teachers

Gifted students need to see that struggle is part of learning. Show them that even the brightest learners benefit from persistence and risk-taking.

Build routines that make resilience visible. Quick reflections, class discussions about mistakes, or check-ins using the Learning Pit all help normalise challenge. Start with the free Growth Through Challenge Poster Pack with 10 printable posters to make resilience visible in your classroom.

Keep challenges meaningful but safe. Offer puzzles, Thinker’s Keys, or tiered tasks that stretch students without overwhelming them. For a ready-made option, explore the Daily Challenge Bundle, which provides consistent enrichment activities that help students practise persistence and resilience over time.

Model self-compassion. Let students see that it is okay to be kind to yourself when things do not go perfectly. This gives them permission to treat themselves the same way.

Resilience is not taught in one lesson. It grows over time through small daily experiences where effort and persistence matter more than perfection. For more practical tools, browse the full store of enrichment resources designed to save you time and challenge your high-ability learners.

Why do gifted students fear failure?

Gifted students fear failure because they often link their self-worth to perfect outcomes. Even small mistakes can feel like proof they are “not really gifted”.

How can I show my class that struggle is normal?

Display the free Growth Through Challenge Poster Pack in your classroom. Each poster uses a powerful quote to show that while challenge feels tough in the moment, it leads to growth in the long run.

What activities help build resilience in gifted learners?

Daily puzzles and Brain Strainers

Thinker’s Keys prompts

Reflection journals

Group discussions about mistakes

What if I want more tools to save time?

Explore the full store of enrichment resources for ready-to-use puzzles and activities that challenge high-ability learners and reduce your planning load.

References

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Gross, M. U. M. (2004). Exceptionally gifted children (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Neihart, M., Reis, S. M., Robinson, N. M., & Moon, S. M. (Eds.). (2016). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? (2nd ed.). Prufrock Press.

Neumeister, K. L. S. (2004). Understanding the relationship between perfectionism and achievement motivation in gifted college students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(3), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620404800306

Nottingham, J. (2010). Challenging learning: Theory, effective practice and lesson ideas to create optimal learning in the classroom. JN Publishing.

Ronksley-Pavia, M. (2015). A model of twice-exceptionality: Explaining and defining the apparent paradoxical combination of disability and giftedness in childhood. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(3), 318–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353215592499

Ronksley-Pavia, M. (2020). Invisible twice-exceptional learners: Understanding the paradox of exceptionalities. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(4), 663–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00362-w

Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617739704